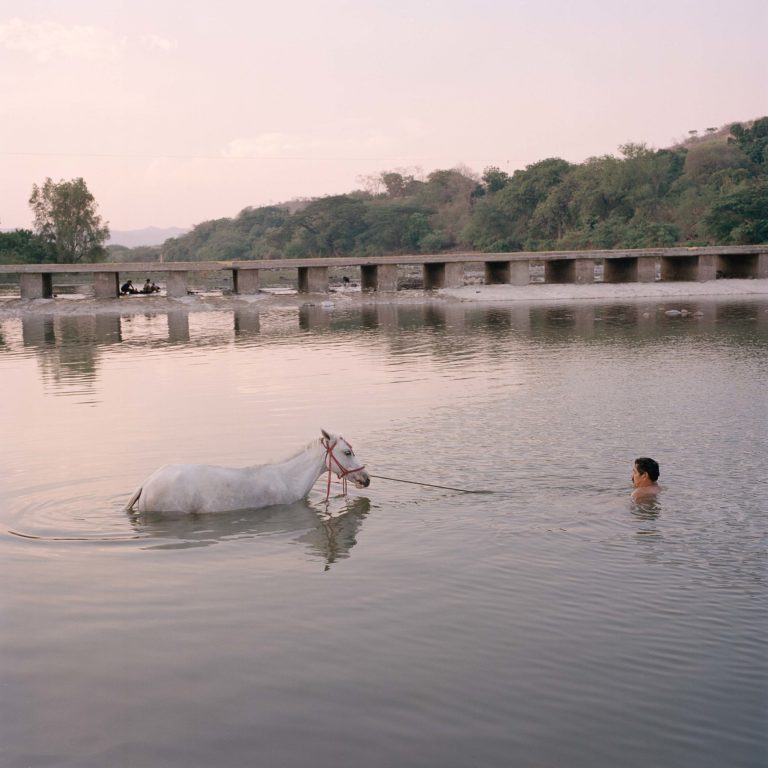

Shot on assignment for The California Sunday Magazine, September 2019

Te espero como la lluvia de mayo. I wait for you like the rain of May — a popular refrain among farmers in Central America, where the first rainfall in May long signaled the end of the dry season. But over the past decade, in what is known as the Central American Dry Corridor — a vast swath that stretches, unbroken, from Guatemala to northern Costa Rica — the rain is no longer guaranteed. Farmers who used to count on two harvests every year are now fortunate to get one.

In southern Honduras, valleys that were once lush and fertile are now filled with stunted cornstalks and parched riverbeds. Adobe shacks erode on mountainsides, abandoned by those who left with no intention of returning.

The droughts have forced entire generations to migrate in search of jobs; left behind are the elderly, who often care for grandchildren when their parents depart. “You can’t make a living here anymore,” says José Tomás Aplicano, who is 76 and a lifelong resident of Apacilagua, a village in southern Honduras. Aplicano has watched as countless neighbors, and his own children, moved away. His youngest daughter, Maryori, is the last to stay behind, but he knows she will leave as soon as she finishes high school. “She has to look for another environment to see if she finds work to survive,” he says.

Many head north; U.S. Customs and Border Patrol data shows that migration from the Dry Corridor has spiked over the past few years. Some spend seasons harvesting coffee or sugar cane in less affected areas of the country. Others move to the city, lured by the prospect of a factory job with steady pay.

Words by Jeff Ernst